Greetings from Overtown

Racial segregation through redlining has impacted housing, climate and the health of Miami’s Black population.

Published on May 30, 2024

Looking at the history of Miami also means looking at the history of racial segregation.

It was between 1894 and 1895 that the lands of South Florida began to attract those who, also seeking warmer lands, fled from ruined crops to settle in a new, friendlier territory. These new and better lands were named the City of Miami in 1896, as scholar Marvin Dunn of Florida International University documented.

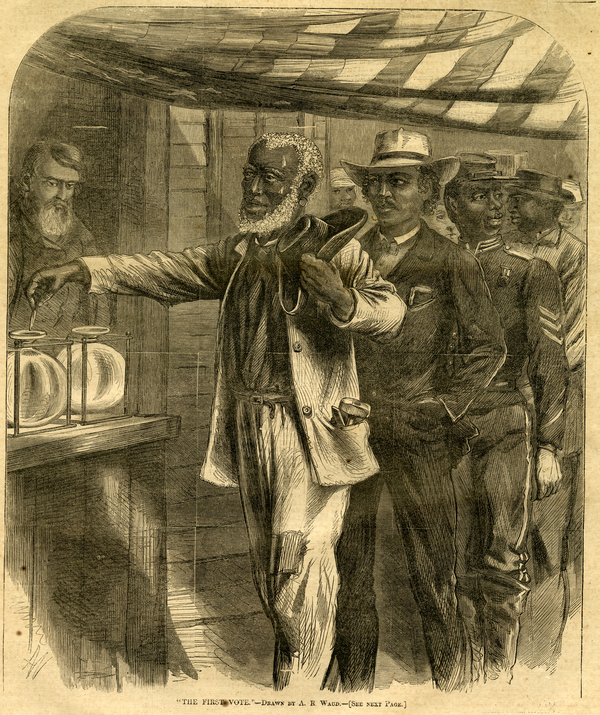

Telling the history of Miami is impossible without talking about the history of the Black population in South Florida. As Dunn explains, when Miami was seeking city status, they sought the help of the Black population, originally established in a designated area known as Colored Town.

The Black population designated to inhabit Colored Town represented up to one-third of the new residents in the area. Without them, it was impossible to grant city status to the new lands offering a better climate and quality of life. It was then, for a brief moment in history, that the Black population was granted the vote to officially make these lands a city.

Perhaps it is not so surprising, then, that the first name to appear on the city’s charter belonged to one of the suburban residents: Silas Austin. And, paradoxically, it is also not a surprise that, after casting their votes, the Black population was once again excluded and degraded in their status as citizens.

This was not the only time the Black community was given the right to vote only for it to be taken back right away. Three years after the city charter was signed in Miami, the white inhabitants wanted the county seat to be moved from Juno to Miami, needing the Black votes again to reach their goal.

This dynamic was not limited to using the Black population as a bargaining chip for the interests of the white population, but, as something considered natural at the time, it extended to all aspects of daily life.

While white business communities expanded rapidly from 1896 through 1926, on the other side of the railroad tracks, the buildings in Colored Town were made of wood and in dangerous conditions. They seemed to be a century behind.

In addition, regardless of the black folk amounting to almost all of the physical laborers used to build the city, no black person could operate a business outside Colored Town. Also, they were not allowed to operate a business that catered to white people, although white merchants could operate freely in Colored Town. The basic city services in Colored Town were scarce, the streets unpaved, and the houses in deteriorating condition. These resulted in many challenges in the community, fires, lack of adequate sanitation facilities, and an inability to improve their situation.

A ray of hope

Even in these oppressive business conditions, some black people succeeded. For example, D.A. Dorsey is known for being the city’s first black millionaire. When he arrived in Miami, he noticed there was a vital need for housing in Colored Town., so he had the idea of building small single-family homes on land he purchased, renting them to newly arrived black folks who were in desperate need of housing.

With the income from renting his properties, he acquired money to build new houses and a hotel, building his own home at 250 Northwest Ninth Street in 1913, still preserved to this day by the Black Archives.

By the 1900s, Overtown had grown into a vibrant community. There were many successful black business owners, to name a few, R.A. Powers, a furniture salesman, or D.D. Cail, who rented houses, operated a restaurant, and owned a packing house on Dixie Highway. Black communities from all over Miami, namely Coconut Grove and Lemon City, would travel to Colored Town for shopping, business transactions, and their booming entertainment industry.

There are many more names on this list, like the founder of The Lyric Theater, Geder Walker. The Lyric opened in 1913 and quickly became the major center of entertainment for black people in Miami. On October 16, 1915, the Miami Metropolis described it as, “possibly the most beautiful and costly playhouse owned by colored people in all the Southland”. It is the lone surviving building in the district known as “Little Broadway”, still in use to this day by the Black Archives.

From the 1930s through to the 1960s, Colored Town was in its Heyday. The streets were bustling with music, lavish cars, perfumed men and women wearing stylish clothing, and frequented the clubs and restaurants along the Avenue. Despite the Ku Klux Klan going rampant, many white folks crossed the railroad tracks to frequent the night spots of Colored Town. At its peak, a few black business owners became very wealthy. Doris Edgecombe works at the Greater Historic Bethel AME Church volunteering with EZRI to feed the homeless. She moved to Overtown over 70 years ago, and shared how she has seen the neighborhood change.

As she says, it is not like how it used to be. By the 1950s, a large portion of the middle-income Black community had moved North from Overtown to the new developments. In the mid-1960s, Overtown began to lose its luster.

When the expansion of downtown Miami led to the Interstate 95 expressway, which was completed in the mid-1960s, it ripped through the center of Overtown, wiping out housing as well as the black business district. The population of Overtown before the interstate was around 40 thousand and less than 8 thousand were left by the mid-1990s. Below you can move your cursor to see how Overtown was cut through by I-95.

All these displaced people faced policies that instead of helping them, closed doors and denied opportunities. The strategy promoted by the National Housing Act, also known as redlining, systematically denied access to populations based on income and, primarily, race. Although this was outlawed, its effects were rooted deep, and segregation in Miami took on a new form.

Climate, money define the new town

Climate gentrification will displace one million people in Miami alone. According to the Frontiers in Climate Organization’s definition, “climate gentrification refers to the ways that climate impacts may contribute to changes in community characteristics and potential displacement of vulnerable residents through changes in property values.” Without a doubt, the world, and especially Miami, has entered a new reality and a new era that is impacting the most vulnerable.

Historically, Miami was a segregated city, this would mean a clear and tangible separation between black and white neighborhoods. Until the mid-60s and the assassination of Martin Luther King, black people were required to present a temporary ID to enter white-considered neighborhoods to work and earn a way of living.

In the 1930s, a discriminatory housing practice known as redlining emerged. Color-coded maps, created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, divided neighborhoods into four colors based on perceived risk for mortgage lenders. Green (A) being the best and (D) red the worst. Historically, redlining maps perpetuated racial segregation and negative stereotypes about them. However, that has changed because of climate.

The graphic above was made by Christina Nunez, an independent writer specializing in weather and climate studies. She publishes scientific articles on National Geographic’s website and in other media organizations.

Floods, fires, sea level rise, and other natural disasters affecting Miami have forced residents from historically A-graded areas to relocate to neighborhoods like Overtown, which is better positioned to handle sea level rise. This influx has negatively impacted longtime Overtown residents, leading to a sudden and drastic increase in the cost of living. Nowadays, some houses in Overtown can reach $500,000, a price unthinkable and unaffordable for most of its original residents.

As sea levels continue to rise, coastal buildings are and will become uninhabitable. Therefore, those living in historically A-graded areas are moving to neighborhoods like Overtown, forcing residents who have lived in these neighborhoods for a long time, to move to areas that are more economically accessible. In other words, as they explain in the following video, they have had to leave their homes.

According to the Overtown’s Environmental Impact Statement from 1982, the U.S government knew about the air quality conditions and noise levels that would result from redeveloping the area for the rich migrators, and all the negative effects the residents of Overtown would face. The report also acknowledged the negative effects on the health of Overtown residents, who would be exposed to continuous construction and proximity to main roads. These conditions later lead to serious health issues such as asthma, cancer, and heart conditions.

Side Effects of Redlining

Redlining is a key determinant of quality of life in present-day neighborhoods. Recent analysis proved that redlining supported racialized access to healthy environments. Redlining destinations are usually associated with lack of green spaces and tree canopy, urban heat exposure, and health conditions such as asthma, cancer, and adverse birth outcomes.

In the case of Overtown, thanks to the Final Environmental Impact State of the Overtown Station Area Redevelopment from 1982, mentioned prior, there is proof that the air pollution conditions are high due to I-95 and other factors. On top of that, asthma occurs at a higher frequency and with more severe diseases in people of African ancestry, as proved by scientific research from the University of Chicago. Also, Schuyler and Wenzel’s research demonstrates grade D neighborhoods suffered from carbon monoxide, sulfur, and volatile organic emissions. These poor air quality and poorly controlled asthma disproportionately burden Black people.

Their research results proved that the worst asthma-related outcomes and inadequate delivery of asthma care occurred among participants from grade D neighborhoods: besides that, the lack of trees means there is less filtering of air pollutants that worsen this community’s health.

Further research conducted by Swope, D-graded areas had 16.21% less tree canopy coverage than A on average in 2011. The figure below compares Overtown, a formally D-graded area, and Coral Gables, which is made up of mostly A-graded and B-graded areas.

The Heat Factor

According to the study The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to Intra-Urban Heat, published by the Health World Organization, the increasing intensity, duration, and frequency of heat waves due to human-caused climate change puts historically underserved populations in a heightened state of precarity.

Steadily increasing warming trends due to global warming are intensifying already higher temperatures in heat island areas. Heat islands are described by the United States Environmental Protection Agency in 2014 as urban areas where structures such as buildings, roads, and other infrastructure which absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat are highly concentrated and greenery is limited. The research by Scotland revealed that urban heat islands in the United States have resulted in part from the effects of redlining.

Urban heat islands are associated with increased energy consumption and air pollution, worsening water quality, and health risks. These are all things that Black communities are already predisposed to due to past segregation. Furthermore, a recent nationwide study indicates that African Americans have the highest surface heat island intensity exposure compared to the White population.

Additionally, African Americans are at greater risk of heat-related mortality than other racial groups. There is a link between the rise in the prevalence of kidney stones and the increased temperatures in neighborhoods affected by redlining. Additionally, the research by Jackson states that compared to White Americans, African Americans are 40% more likely to have hypertension, experience twice the incidence of stroke, and develop kidney disease at a rate four times greater.

African Americans also suffer from higher rates of diabetes. This higher prevalence of heat-related morbidity among African Americans is not due to genetic differences, but rather disparities in health and living conditions, such as residing on a heat island.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Nevertheless, their hope is not lost. God has got me, Doris Edgecombe said. Those words reflect how the residents of Overtown firmly believe that their situation can improve. With their faith as their pillar, even in moments of apparent abandonment, they power through. The people over at the Southeast Overtown/ Park West Community Redevelopment Agency (SEOPW CRA), The Empowerment Zone Reentry Initiative (EZRI), where Doris Edgecombe volunteers to feed the homeless, The Green Haven Project, a non-profit that provides green areas, fresh food, and education on horticulture and nutrition, all work to empower, and revitalize the community in Overtown. Moreover, they have us, the people who will not back down until their voices are heard, their amplifiers. Because, in the end, all that they need is for someone to hear them and help them.

Climate Change and Climate Gentrification are global issues affecting everyone and ordinary people seek assistance, be it as amplifiers or educators. This is why we can not turn our backs on them. They need our help, and global issues require global assistance. In the end, everyone has the right to live with dignity in a proper home with all the necessities covered.

Even though the clock is ticking, there is still hope, and it is in our hands to take action today.