Welcome to Doralzuela

Miami is a hot spot for Venezuelans who have fled from corruption, persecution and one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world.

Three generations of the Montbrun family, originally from Venezuela, now call the United States home.

Published on May 30, 2024

Miami has become the hot spot for thousands of Venezuelans who have fled from corruption, persecution, and one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world.

But behind each number, there’s a face and a unique story. In this new environment, 1,609 miles away from home, they’ve rediscovered their cultural roots and national pride.

Once a rich nation

Venezuela was once the wealthiest country in Latin America in the 20th century, as noted by Ricardo Haussmann and Francisco Rodríguez in their book Venezuela Before Chávez.

It enjoyed a stable democracy, had the largest oil reserve in the world, attracted various international businesses, and received tourism from all around the world. It was known as “Venezuela Saudita,” the tropical paradise that everyone wanted to experience, whose streets were filled with fancy cars and luxurious shops.

With this lifestyle they enjoyed, Venezuelans never thought of leaving. But today, they are part of the largest displacement crisis in the world, with a migration of 7,7 million people, as reported by the UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Waves of migration

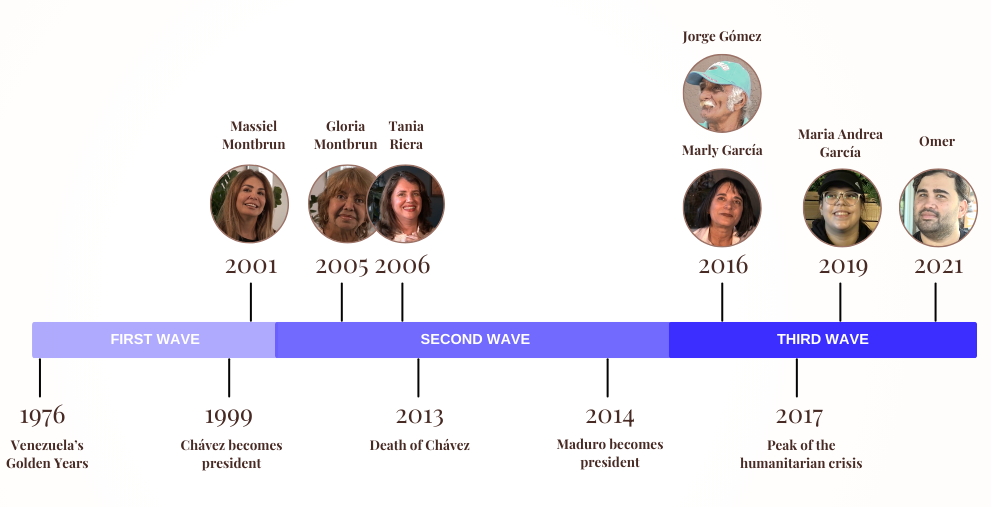

The displacement process can be distributed into three waves of migration: the first one took place in the early 2000s, was followed by another one in 2015, and finally by a third one in 2017-18. Each was motivated by different causes, moved people with diverse backgrounds, and directed people to various countries around the globe.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, when oil prices plummeted in the 1980s, inflation started to rise and the country found itself in debt. At that moment, entrepreneurs and high-class individuals started moving elsewhere, but in very reduced numbers. When the politician Hugo Chávez started campaigning to become president in the 1990s, more people started getting suspicious about the situation and decided to leave.

Early birds

In sight of Chavez’s rise to power in 1999 and his first years of government during the early 2000s, the first Venezuelans began to leave the country. They came from favorable economic backgrounds, had good levels of education, and left because of the degrading economic situation and political uncertainty. They felt persecuted by Chavez’s government policies which threatened private property and family assets, according to Xchange Research on Migration.

The majority moved to neighboring countries, such as Colombia, and to the United States. Thanks to their personal assets and family ties, they obtained residence in those territories. Thus, their process of integration was smoother and less chaotic than those of the following waves.

Escaping oppression

After Chavez died in 2013, Nicolás Maduro became president in 2014. Massive protests broke out throughout the country and were met with violent repression from the government. Thousands of people were persecuted and tortured for demonstrating any kind of opposition towards the new government. Additionally, insecurity grew exponentially, basic goods started to disappear from the markets, and inflation continued to rise.

All of these aspects triggered the second wave of migration. It was composed of professionals and people who had sufficient resources to start a life outside the country, but it also included more middle-class citizens, as well as students who were sent by their parents to study at international universities, and Colombians who had migrated to Venezuela years before.

Los Caminantes

As the political climate showed no improvement, the despair of Venezuela’s population reached its peak in 2017-18, initiating the most complex wave of migration. It moved highly vulnerable groups of the population who were victims of the humanitarian crisis. These left the country on foot or by bus because of their lack of economic resources, and went to South American countries, and to the United States.

They didn’t integrate easily into their new destinations. Without family ties or assets, most remain undocumented, generally unstable, and with weak health conditions.

Where migrants become Venezuelans again

Most of the migrants who arrived in the United States established themselves in South Florida, especially in the city of Doral, also known as “Doralzuela”. As of right now, they represent approximately 30% of the suburb’s population, according to the 2020 US census, and have created a hub where their culture and pride come to life. The streets are filled with restaurants selling arepas, empanadas, and tequeños, Latin markets that sell imported products, and families that enjoy a healthy environment where they don’t worry about insecurity, water and electricity shortages, or the supply of basic goods to survive.

Grace Odom, 19, is one of the inhabitants of this vibrant city. Born in the United States and raised by her Venezuelan mother Massiel Montbrun who migrated in 2001, she has grown up with a mix of cultures that have shaped her identity. Her home embodies the situation of many Venezuelans that have created safe spaces to protect their traditions, where all the struggles they used to experience fade and the hope for a better future awakens.